Category: Cyrelian

41. Cyrelian–Awakening: Jarl’s Longhouse 1

At first I did not know where I was.

The words of a religious service echoed about me, maddeningly familiar.

Was this some rite I knew?

There was a cantor– a human lady with a heavy northcoast accent– but the cadence of her reciting-tone rendered her phrases nearly incomprehensible to me. This tongue-song was wholly foreign to me; I could barely recognize these words as Cyrodiilic.

How was it that I could anticipate each response?

Each phrase leaped unbidden to mind, like the quick flash of minnows darting through clear water. Where did this knowledge come from?

My own thoughts were sluggish and honey-thick, as if I were yet dreaming. Word for word, my lips could frame each versicle’s response, though I stumbled and hiccuped on the timing. No, she was not finished; that was merely the shift to the flexa; there was going to be another verse before the change to the mediant. Four more words for the termination and we were on to the next–

What music was this?

I struggled to comprehend.

I knew, instinctively, that I had never heard this rite before. I knew that this rite was wrong. Yet I knew by rote each and every syllable of the proper response.

Syllables and words that were almost comforting, despite the uneasy distaste I felt; I had felt this unease before. Familiar words that I had forced myself to review over and over again, no matter that they made me feel uncomfortable; a lie. Easy words to follow.

As easy to review as the short paragraphs laid out in a service manual.

In the chapter entitled: “Regarding Heresy.”

My eyes snapped open.

I was in the presence of the enemy.

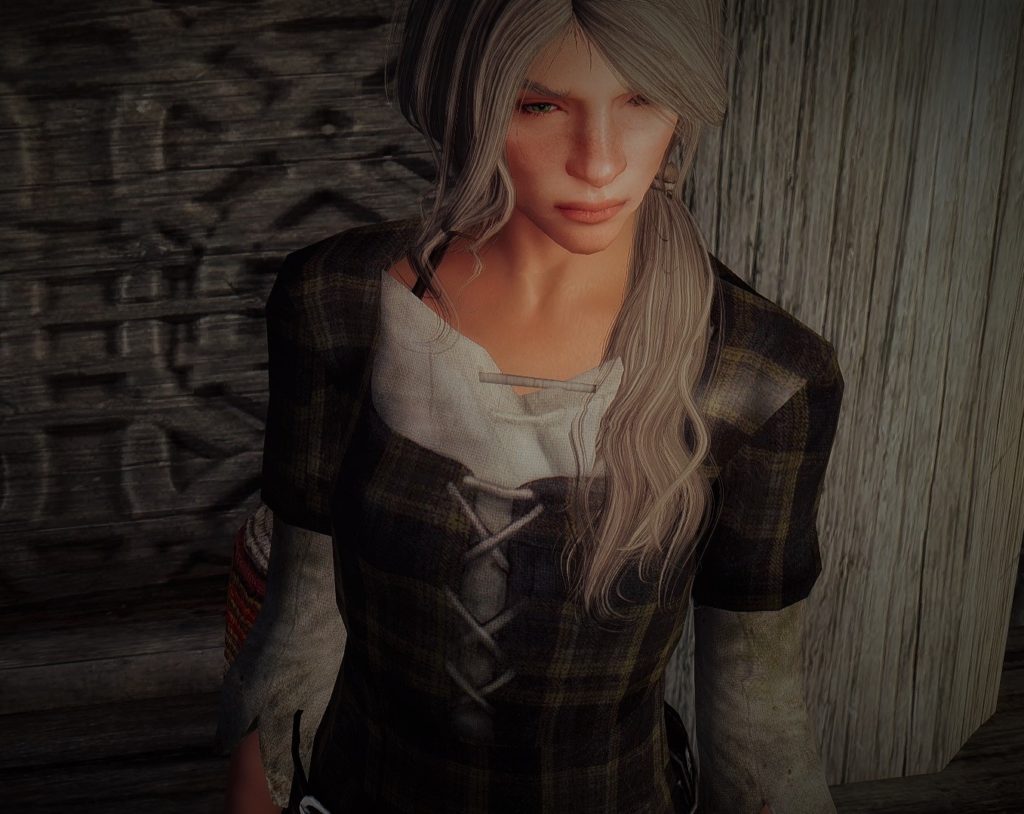

“Don’t,” came a Nord-accented, feminine voice.

The same voice?

I gasped. I was too dry to scream.

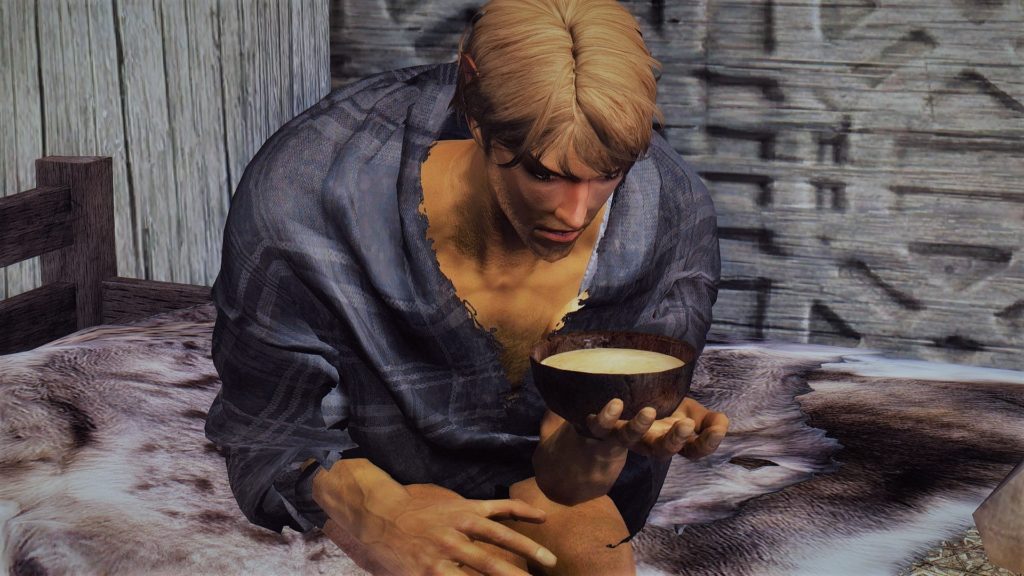

“Don’t try to get up. You’re still very weak. Here.” The wet rim of a wooden cup pressed just below my mouth as my head was steadied. Was it a drug? Was it a poison?

My training drummed in my ears: Turn your face away. Do not accept it. You do not know what it might be– something to sap your will; something to eat through your flesh. My arms and legs ached from the rack; from the…

I was fading down to the darkness again.

As soon as the liquid touched my lips I sucked greedily at it, drinking in great noisy gulps. Oh, I was dying of thirst and it was not nearly sufficient. I choked and coughed. The cup was taken away, and I was chided for my haste.

A breath or two– I had control of myself now; I would not– When it was brought back to me, I succumbed again, trying desperately to grasp it. I could not move my hands. They were bound.

Laughter, peals of it.

Who were these people? What kind of terrible people allow their small child into a prison-chamber?

“Look at this, Yllga. He couldn’t even keep his eyes open yesterday. Could you hand me that towel?” Something wet, scrubbing at my cheek.

And– blackness.

“Bring that over and give it to him right now– I don’t wish to bring him up for too long.”

That was an Altmer voice. I had been warned of these people– the tainted ones; the recusants and unbelievers; the corruptors-of-blood; the betrayers who live to infiltrate us and– he had the uniform. A lie. A trick. The misbelievers steal this things, to lull us into complaisance.

Once more I refused.

The Altmer made an exasperated noise and got to his feet. “Give it here,” he said.

A firmer hand grasped my jaw. “Open,” I was commanded, and I did, once the merciless thumb jabbed into the nerve plexus there.

Something cool and tangy was dolloped into my mouth. I should have refused. Food is the body’s strength and when one is wholly trapped, it is time to let the body fail. It is one’s duty to evade questioning by any means. I should not cooperate with this, this torment that they meant to do to me. I must try to get up. I must seek the escape; there, I could see it. A door. I strained to get up, but my legs were leaden, and my left wrist affixed. I could not get the necessary leverage–

“If you do not eat, you will die,” the mer said, annoyed.

That was as just as well, if it meant there could be no more questions. Strong fingers took hold of my chin and pressed down, painfully. More of the thick stuff went into me. I tried to turn my head, and was prevented.

“Swallow,” directed the voice, and I could not do otherwise. “Open your eyes again. Look at me. I want to know how you managed to bring yourself out of stasis.”

I did not wish to do as the voice said.

I tried to rid myself of the paste in my mouth; but had to gulp it some more of it down rather than choke. I shook my head wildly and coughed to clear my mouth, and spat. Now that it had been commanded that my eyes open, I kept them tightly shut.

Apparently I was a source of great amusement– the child again– but not to the voice; I heard him growl disgust.

The Altmer retreated: “If he’s strong enough to fight me like this, he’s probably strong enough to be left out of stasis. I’ll let you take over feeding him. He’s swallowing fairly well now. Thick liquids are better than thin; but no matter what make certain that he’s fully awake before you put anything into his mouth.”

And, more attenuated– “What IS this substance; I’m covered with it. Will it soak out in the wash? I shall have to speak with Suivari.”

The Nord woman again, rueful: “You really do make a mess, don’t you? Here.”

The wet cloth again, swabbing me down.

“That won’t do any good, Mama– it’s all over the bed.” “So it is,” said the lady, making a few futile swipes at the pillow. “I think I’ll try putting some honey in it next time. Waste of good skyrr, is what this is.”

“He’s just like a big baby, isn’t he?” The bed heaved, as though some large animal had jumped onto it. A mammoth. Or a half-ton sabrecat, perhaps.

“Yllga! Leave the poor man alone, he needs to rest. Come. I’ll let you help me pour out the next batch of skyrr.”

“Hello!”

My eyes slitted open. My head hurt. My mouth was impossibly dry. I was thirsty. I was being forcibly greeted by an impossibly small, brown-eyed child.

“This is Mathilde,” I was told. A doll was thumped up and down next to my face. “She’s a Breton,” I was told, in the same tones as if this were a confidence of deathly import. The doll, I noted, also had brown eyes. And a mule’s ridiculous lop ears. I wondered whether that were some sort of social commentary.

I was much too dizzy and sick for this. My left arm refused to move. With very great effort I heaved myself onto that my side, the world wavering and roiling as if I were on some hellish voyage. I keened and panted in terror whilst the vertigo claimed me.

The woman came in and insisted on administering more of the nasty substance to me, I faded back into fitful slumber. At some point even the stuffed-lump Mathilde must have gotten bored with me, for I noted that she had gone. I could hear the child playing at make-believe, with her doll and with her other things. I noted the odd little whistle of her breath.

When I woke again, I could hear the child again. She sounded like she had a bad catarrh. And she trundled about the room rather than running back and forth underfoot as a child that age ought to. With her slow and careful movements, she was five years old going on three hundred and seventy.

From what little I could see from my vantage, this was most definitely not a prison or a place of interrogation. There were pelts and carpets on the floor. Pelts under me. I could smell bread baking. And, holy sweet Mara, beef stew. This place smelled wholesome, like food cooking, and a place where washing was being done, and–

Relieved, I tried to sit up, and was at once restrained by the bond about my left wrist.

Fear washed through me. No! My first impressions had been correct; this place was all wrong. I needed to keep fighting.

I struggled and floundered before falling back again.

The dizziness claimed me, and then the black fatigue.

An hour later? Days later?

I opened my eyes again, to that serious little face. “My papa says that you’re a warning against offering hosp.. hosp… hostality,” said the child, with a degree of gravitas that a new-minted Justiciar could only dream of mustering. “He said always ask more questions before you make binding promises.”

Experimentally, I tugged my left wrist. The binding was solid leather and had little slack. I was caught. The buckle was on the side where I could not readily reach it. It was too stiff for my weakened fingers. There was no hope for it; I was bound fast. There was no way that I was going to be able to get free.

I gave it my best efforts.

“Talos wept, what a pain in my tail you are,” said the Nord lady, sometime later. “Yllga? Why did you not call out for me, child? Agh. How did you get your legs off the bed?”

After some struggling and heaving, she got my body back up on the bed, and straightened my limbs back into the position in which she felt they belonged. She stood still a moment, panting and holding her belly.

“You son of a boot,” she said, when she saw me watching her. “You were awake? You could have helped!” She leaned down next to my ear, and whispered “Next time I’ll let you hang there till your arms go black and dead and there’s nothing to be done for it but wait for the maggots to come.”

“Oooh,” said the child, impressed at her severity.

But a lady who said something like that in all earnesty would not be wasting further time on me. Would she? Certainly she would not be worriedly chafing at my hand to get its circulation to come back up. Nor would she take the time to tuck the furs all around me, and to re-settle the pillow under my head for my better comfort.

Despite all this tender care I had the distinct sense that this was not the first time that I had annoyed her.

Why couldn’t I keep my eyes open?

I had no idea what day this was. This was worrisome. I slept.

At long last these people forced a reaction out of me; I emitted an awful groan.

Would this torture never cease?

“Think I’ll try broth next,” said the woman, judiciously. “Skyrr takes some getting used to.”

I was out again.

Were they drugging my food? It didn’t matter; the woman didn’t let me refuse, and I was hardly awake long enough to protest.

Moments?

Hours?

My back and legs ached terribly.

I had been here some while. It was long past time that I set myself free. I sought for the buckle, and… It was too much effort, of a sudden. I needed to gather my strength. Carefully I eased myself back so as not to trigger the maddening, horrible disorientation and dizziness.

I shut my eyes for just a few moments.

Or days.

It could have been weeks.

I really have no idea.

I had to piss.

This was going to be close. I managed to get fold my hand enough to slip it halfway out of the bod and pulled frantically at the buckle-strap. Loosened just in time, and thankfully there was the necessity-bucket kept tucked beneath the bed, it was right there…

“How did he do this?” said a querulous new voice.

Male, irritated.

An odd accent. I attempted to get a glimpse, through my eyelashes. Dunmer? I didn’t think it was a human voice.

“At least he didn’t make a mess,” said a heartier male voice.

Nord, amused.

Even with my eyes shut I knew he had crouched down to have a look.

“No point in doing that strap up again, it seems. It just upsets him. Leave it for now.” That was a command.

“If you’re convinced he’s not going to get out into the cattle pen again and freeze half to death,” said the Dunmer, dubious.

“I’ll talk to him,” promised the Nord.

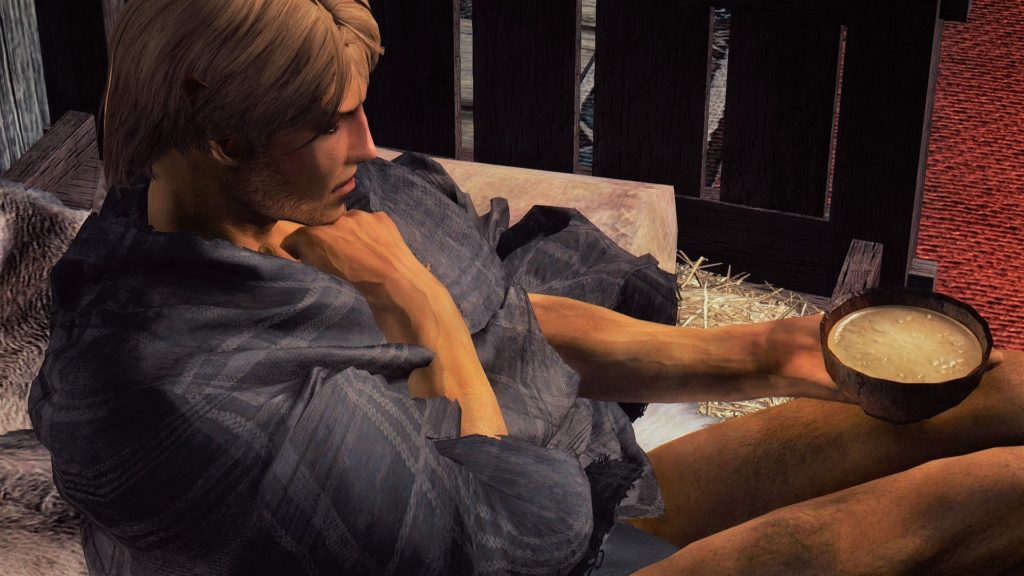

Together they heaved me back up onto the bed, carelessly tossing the furs back over me. The ropes of the bed creaked in protest as the Nord sat down beside me. His warmth felt good. Soothing. A broad hand patted my cheek.

“By order of the jarl,” the man said. “No leaving this bed until that elf wizard says you can. Use the bell. Understand?”

I realized that there was indeed a bell, that was the extra weight I had felt at my left wrist, beyond the restriction of the strap.

He wasn’t going to leave, I realized. Not until I opened my eyes and looked at him.

When I did, his hand stayed put, fingertips cupping my cheek. The room was dim, but the light from the fire limned his beard and hair; darkest copper-red, lit with rose-gold. Beautiful.

And that face– “I’ll do whatever you want me to do,” I promised immediately, and was treated to a broad smile.

Oh, that was unnecessary. I was already in trouble.

“Good,” he said. “Stop making such a fuss. Nobody here is going to hurt you. And you’re making a great deal of work for Malur and Thaena.”

He took my hand and examined where the leather had scuffed up my wrist. “I’ll leave this off,” he said, consideringly. “But I need your word that you won’t try to go outside. In this weather, that’s certain death.”

I agreed, happily, and let my hand slide into his. I looked up at him.

“Stay,” I urged.

He laughed merrily and pulled the fur blankets over me. And continued to laugh at me as he walked away.

“Seloth?” he called, still chuckling. “You’re not going to believe this…”

“I’m hungry,” I said immediately.

“Keep your shirt on,” advised Thaena. She brought over a small bowl.

“This is just the broth,” she said. “We can’t give you the meat and vegetables until they stew down a little more and I can mash them up. It will be an hour or so.”

I drank it off immediately. “Is there more?” I demanded. “Why do I have to eat this thin stuff? Can’t I have bread, or meat?”

There was a delicious thick potage on the table, and wedges of aged cheese, the very sight of which made my mouth weep. I would kill for one of those crisp apples, bursting tart over my tongue…

“There’s bread,” she said. “Let me bring you some.”

She took my empty bowl and left the room. Would it be possible for me to get myself some of that stew? I could hear the broth bubbling gently in its kettle, and the hearth did not look all that far away. Maybe if I refilled the serving-bowl, Thaena would not notice that I had depleted it?

I was far too dizzy even to attempt to stand… but perhaps I could crawl?

Thaena came back in while I was still parsing the distances. I blinked at her.

Oh. She had taken the bowl away.

It would have been a futile effort nonetheless.

“Here,” she said, giving it back to me; it was bread sopped with goat milk, which should have been revolting. It was ambrosia. I wolfed it all down before she even had a chance to turn away.

“Does it have to be all wet with this stuff?” I asked. “Could I have the rest of the loaf?” And– “Is there any ham, maybe? Or cured fish? I want some of that stew–”

Thaena scowled at me. “You’re supposed to be taking liquids,” she said, severely. “That’s what he said. And I’m not going to bring that Thalmor down on us because you talked me out of doing as I’ve been told. I’ll get you some more skyrr.”

I groaned in protest.

“With honey,” she added. “And if you’re good, maybe some watered mead.”

Exceedingly watered mead, but I resolved to refrain from further complaint. As long as it wasn’t skyrr.

When she came back, I asked: “So how is it that Thalmor give orders here?”

I indicated the large Talos shrine by the railing, the one that I’d seen previously. The rite that I had overheard– that must have been a small family ritual, not the great convocation of my nightmares.

I drew my knees up, testing myself.

I would have to sit up in a moment. My back hurt from disuse, I realized. And my legs. All of my muscles felt weak. Even my hands, when I flexed them.

“The Thalmor don’t. The Advisor does. For you–as your physician. Also he says that he is still waiting on an official determination of whether there is to be a recognition of sovereign status or whether we’re going to be considered a province-in-rebellion and as such remain subject to the ban as outlined in the Haafingar Attachment,” Thaena said.

She said all of that straight out with no hesitation, just as easily and casually as a quick comment that it was snowing.

I blinked.

“Ahh,” I translated after a moment– “The Advisor’s not volunteering to stick his neck out one way or the other for the axe.”

Whether it be Ulfric Stormcloak’s, or that of his own superiors.

Thaena gave a little snort of agreement: “Ancano said that since Dominion evidently can’t tell its arse from its elbow– that he has no great confidence that its left hand knows what its right hand is doing. Says he’s waiting on specific orders.”

And that was the final piece of evidence that fell into place: these people meant me no harm. They had been telling me the truth.

For I well remembered when that question had first been asked, at one of Elenwen’s daily briefings: What should we do, about this rebellion? Skyrim’s Justiciars had been waiting on a response from Alinor for quite some time. Policy decisions take time. The Thalmor Advisor to the Archmage of the College of Winterhold was a lone operative, whose duties were supposed to be social and diplomatic. Even the most rabid of the sectarians would not expect a mer in a position such as this to strap on armor and attempt to conduct law enforcement duties on his own.

Would they?

But if someone had– that would certainly explain his comments.

How had he come to be so unguarded with these people?

And of course if a Thalmor mage was being allowed to see to me–or if this household were tending me on his behalf–then it followed that I was not, in fact, a prisoner. I regarded her more closely, this seeming-housewife, with a smear of flour on her tunic and her hair coming down from its messy pigtail.

“Where did you take your training?” I asked. Legal training, I meant. It was clear now, what she was here.

“Father’s knee,” Thaena said. “His sister was the law-thane for the Pale; and then my mother, and after she got sick it was me. Now I’m here with Korir.”

She finished with the foul paste that she’d been mixing up and handed it to me. They’d been cramming it into me for days; surely if cut open, my liver would bleed skyrr. This batch was orangey-grey with mashed cloudberries and lumpy with gods knew what else– it looked singularly unappetizing.

My stomach growled, and I no longer cared.

“This is really good,” I said, astonished. “What did you do differently?” It was embarrassing how badly I craved food once I tasted it.

I found myself sucking at the spoon and licking both it and the bowl fully clean, as if I were a starved cat.

Thaena was watching me, amused: “I put some soaked dried apple and toasted oats into it,” she said. “Thought maybe you needed something a bit more substantial.” She shrugged. “He said that anything we gave you had to be liquid. Let me mix up more.”

When I received my new batch of heavenly slop, I tilted the bowl, experimentally. The sludgy substance within considered for a lengthy moment and then consented to slide downhill. Grudgingly.

“Liquid?” I queried, in disbelief. If I overturned the bowl and shook it would take a moment or two for this stuff to fall out.

“None of it’s actually solid,” said Thaena, shrugging.

I looked up at Thaena: “Are you certain it’s a good idea to try to rules-lawyer a senior Thalmor official?”

“You have no idea,” she said, with a secretive little smile.

Thaena came back in a few minutes, to retrieve the bowl. “It’s good to have you back with us,” she said. “Ahtar said you were a clever one, when you–”

She tsk’d reproof.

I had already slumped sideways. Despite the quick flash when she’d said the name, it had become too much effort to raise my eyelids. I could barely feel her prising the empty bowl out of my grip.

The world faded.

40. Ancano–Consult: Dragonborn Gallery 3

Auryen regarded him for a little while, then appeared to come to some conclusion. He left the room and returned a minute or so later with a couple of bottles of small beer in each hand. It was ice-cold, too, thank Auriel. It was briskly carbonated, crisp, and just barely alcoholic; it was divinely refreshing.

“When you saw him previously, what did he look like?” asked Ancano.

“Prior to this summer?” Auryen clarified. “He always used to be in attendance on Elenwen or the Ambassador, sometimes in blacks, sometimes filling in for one of the soldiers. I thought he might be one of her aides. Let me see…” he glanced about the room. “What a shame, I don’t have any of the pattern-books here—but you know how it is. One gets to a certain age, and just maintains the fashions of one’s youth.”

Ancano, whose looks were often attributed to cosmetic enhancers–he had never taken advantage of any–kept silent.

“Let me think,” said Auryen. “It was definitely a late-fall mode, one of the soft-contrast ones. Autumn Despond? Leafs-last-breath? I’m really not certain.” He frowned. “Hair sort of a dead autumn-leaf color; not quite auburn. A great deal of freckles. Eyes—hazel or green or brown. Fairly well done for what it was; thought he had a good eye for what would pass, at a distance, as Bosmeri. If there weren’t other people around, for one to gauge size. Plenty of Bosmer in Skyrim. No one takes notice of them. Or perhaps as an outsize Breton, to the undereducated.”

He drank again. “In dim light, maybe even a Nord, if he kept a hood on.”

Ancano asked another question.

“When’d I see him last on duty?” Auryen frowned. “Hard to say. Elenwen had him at court a few times not too long after all those funeral obsequies finally concluded. Let’s see…I came in on a land-grant petition the early part of last fall– he was in Nordic court dress bearing the Thalmor sigil, and I believe he had been sent there to provide some of the break time’s informal entertainment. He played the flute. Seemed in good fettle.” He smiled. “There was this persistent rumor going around about him and a couple of Dibellan priestesses, but I wouldn’t credit any of it. Pretty wild stuff. He didn’t seem the sort.”

“Oh—I should say. High-noble caste mark—“ Auryen Morellus traced the pattern of it on his own face; Ancano nodded– it was the most common one of that status; not much help there. “Orondil had him out and about running a few minor errands—I got most of this from Orondil, you know. He’s the one who was out looking for him. Made it sound like it was only unsanctioned leave, but it was plain he was severely worried.”

Ancano reached for another bottle. “My preference would have been to bring Orondil in on this fully,” he asserted. Auryen had disagreed with him about this earlier, vociferously.

“I chose not to,” said Auryen. “Because of what happened later. I spoke to this Cyrelian, you know.” He regarded the crumbs on empty plate, sadly, and excused himself. When he returned, he was bearing a platter with more crème treats– as well as rusks and cheese and preserved quinces in syrup. Rosy-pink sliced ham sandwiches with Jehennan hot mustard and some crisp green apples.

“Sorry,” Auryen said. “I couldn’t slow down long enough to eat earlier.”

“It was hard to discern details. A warm evening, indoors, and there were a number of other persons present and not much light.” Auryen brooded over this a moment. “Superficial injuries were apparent, yes—bruises all over his hands and wrists. Face and neck. Could be what you described. I want to say that there would have been scratches or cuts, Couldn’t tell you what gave me that impression, though. At one point in our conversation, he became overset and had to go and sit down. I didn’t find that all that unusual, though—“ Auryen looked away from Ancano. “—I had directed him to report back in to the Embassy.”

“Had you?”

Auryen said: “Very clearly he’d been out on frolic for an extended time and was not doing well. Nothing he was saying was making any sense to me– he was almost raving. Accusing the First Emissary of conspiracies against him and so on. Said she was trying to disgrace him so she would prevail on some legal dispute. Skinny, filthy dirty under his clothes– those looked new–his hair was all cut off and matted. He reeked.”

“Like what?” Ancano persisted. Dried blood, the sweetish scent of rot, unwashed clothing, bad digestion– he needed to glean every detail he could.

Auryen’s mouth had pursed up, almost primly: “Like he’d been fending off wild beasts.”

“Wild beasts?” repeated Ancano, with great care.

“Oh, yes,” mused Auryen. “There was no other reasonable explanation for the condition he was in.” He set down the remainder of his sandwich and pushed it away, as though he’d found it suddenly unappetizing.

“I am sorry,” Auryen Morellus added. “I should correct myself. I didn’t send this Cyrelian back to the Embassy. I thought that would have been rather unsafe. Instead I directed him to report to Ambassador Orondil, so that the Ambassador could facilitate his immediate transfer back to Alinor.”

“Too many wild beasts… in the vicinity of the Embassy?”

“There are reputed to be,” said Auryen, who had taken an unseemly interest in whatever dregs remained in his bottle of beer. Or perhaps it was something of interest on its label.

Despite the food, Ancano was too drunk for this; he could not keep up. Not quite.

“So—would that unfortunate circumstance not be something to bring to our ever-so-delightful First Emissary’s attention?” he dared. “Should be well within her discretion.”

“One would think so,” observed Auryen. They were silent.

Ancano coughed abruptly, to signal a change in in this surpassingly awkward subject: “So– did he seem particularly ill to you, when you saw him? Feverish, sweating, or so on?”

“Slow to move around,” said Auryen, displaying gratitude for the shift. Perhaps he was a little drunk, too. “It was difficult for him to rise from his seat, or to sit down. Nothing that would have struck me as unusual for having suffered an ordinary sort of beating.” Auryen frowned. “It was the dinner hour and others were taking refreshment and he was not. He declined. That struck me as odd.”

“And would you have been in a position to note whether he performed any healing spell or anything of the like? Or consumed healing potions or other simples?”

“I spoke with him a few minutes only,” said Auryen. “I saw nothing.”

“Do you know if anyone else healed him?” Auryen Morellus sighed. “Now we come to it,” he said. His lips compressed. “I’m afraid I cannot give you that information.”

Something was odd. Why was Auryen Morellus suddenly so anxious for this healer?

“Likely nobody cares but me,” said Ancano, taking great pains to sound morose. He sighed. “Ambassador Orondil has probably already written him off.”

“Sit back down,” said Auryen, at once. Ancano did so.

Auryen Morellus was thinking. “You need to speak with this person directly?”

“I do,” said Ancano.

“There will be no arrests?” asked Auryen, sharply.

“I wouldn’t have the authority to do so. Nor the jurisdiction, actually.”

Auryen hesitated. “What if you did? Speaking theoretically, mind you.”

“Is this mage a citizen of Alinor, then?” Ancano demanded. That would help him narrow the field, greatly. Auryen Morellus looked even more disinclined to speak.

“I understand that this individual will have no wish to speak with the Thalmor,” said Ancano. “But if I find whoever-it-is, they will at least have a head start. The Justiciars who follow in my wake will not be so gracious.” He leaned forward, intently: “This is not a good prognosis– but if this injury kills him, it will have done so because it was fatal from the beginning. Not because of something a healer-mage did or did not do. And so my report shall state.”

Auryen was silent.

“Please,” said Ancano. “You must know this is why I am here.”

He let that silence fill the room for a few more moments.

Then: “I cannot help him further unless I know what was done for him, or not done. I need to interview that healer so that I can get a better understanding of his initial condition. And–”

“This mage, would they have to be returned to Alinor? To be further interviewed by the Thalmor?” Auryen’s voice was sharper now.

“Absent unambiguous evidence of malfeasance– which there is not–no. I would be more than happy with an interview and an affidavit. Something that I could bring back to Alinor. Assuming the worst–I couldn’t guarantee that there wouldn’t be further questions down the line. Which of course would be coming from the First Emissary.”

“No,” said Auryen. “Any further questions– those would not come from her. This goes higher up than you know.”

There was quiet again. The fire had died down to coals and it was getting chilly in here. The windows showed a greyish light; it was getting on towards dawn. Ancano shifted in his chair. He got up to tend to the hearth, considering.

Before Ancano could ask anything else, Auryen Morellus cleared his throat: “I do have a question.”

“Pardon?”

“Do you have any sense as to what would happen next if the First Emissary were to be recalled? As in– do we think that the Third Emissary would be promoted; or that there would be a pro tem appointment, or whether Alinor would simply replace the entire–”

“Oh. Yes,” said Ancano, standing back up and dusting the remains of bark off his hands.. “That’s an easy answer. Anyone new who came in would without a doubt be far worse.”

“Are we absolutely certain of that?” questioned Auryen Morellus.

“I do regularly review the assignment bulletins and the seniority lists,” said Ancano. “It’s always wise to know who might be after one’s position.”

Or one’s head.

“Far, far worse,” he clarified. “Elenwen can at least be reasoned with, upon occasion. And Rulindil– keeps to himself, more or less. I haven’t had much dealing with our installation in Markarth, but no news is good news from that place. Ondolemar’s star would fall with the First Emissary’s, though, I would guess. She brought him here.”

“Ah. Well, we have a significant problem then,” said Auryen. He brooded over this.

“I’m sorry?” Ancano didn’t follow him.

“This young person is within the requisite degree of kinship to prompt the First Emissary’s recusal on any sort of investigation,” said Auryen. “Much less a death investigation.”

“Hm?”

“Well within,” clarified Auryen Morellus. “You do know the name?”

“I did remark upon the name,” said Ancano. “But you know how it was,” Ancano excused himself. “For about a hundred years everyone was naming their children for Ata-Aldmeris; so I didn’t think it would be all that uncommon a name-construction to encounter. The ultra-orthodox, families desperate to curry favor, and so on. I thought nothing of it.” He regarded his bottle of beer, sadly. There wasn’t nearly enough, and it was by no means strong enough. It was a shame they were out of brandy. “It gave me a terrible sinking feeling, though,” he admitted.

“See? You should trust your intuition more,” said Auryen, expansively. “This Cyrelian’s not just within the requisite degree of kinship– he’s within the first degree of kinship.”

Ancano froze, calculating. “Son?” he hazarded.

“Brother,” corrected Auryen Morellus. “Younger brother by quite a few decades. Oh, my mistake. Second-degree: half-brother. Different mother, of course. He told me Elenwen was actually his heir. To an otherwise male-entailed estate. Fairly substantive one, as I recall. That would make sense given the history of that house–it’s been somewhat infamously locked up in legal proceedings. What I’d give to get my hands on Ata-Aldmeris’ library alone…” he sighed. “Not to mention all the antiquities he collected out of Cyrodiil and Valenwood, before so much was lost in the Anguish. I heard he had the second-biggest collection outside of Blacklight. Though I’d wager that’s an exaggeration. I do hope they have someone looking after all those things… what a pity if they were all ruined.”

Auryen coughed sheepishly: “I’m afraid that I discounted much of what this Cyrelian said as paranoid ramblings; he seemed to have quite a degree of animosity towards his sister. He seemed to believe her directly responsible for his circumstances.” He laughed, a bit deprecatingly. “Certainly he was not feeling well. He seemed to believe that the First Emissary had ordered her subordinates to assault him– either to kill him outright, or to cause him to be discredited and disgraced. How absurd.”

Ancano found himself uncorking a bottle for something to give his hands to do; by no means did he want another cold drink any longer. Despite the rekindled fire, he was chilled clear through.

“Indeed,” Ancano said, in the same light tones, as though he were taking it not-at-all seriously. “But do we really think an investigative team from Alinor would discard any theory out of hand? Even one so improbable? And of course they’d be looking into all of the turmoil–”

He got up to move about the room, pretending an idle restlessness which he did not feel. Frankly, he wanted to run. He settled for pacing.

“Oh?”

“I’ve heard the oddest things of late,” Ancano reflected. “Coming out of this place. Haafingar. None of it made any sense to me. Like, a senior Justiciar turned up on the discharged-dead list with no further commentary. Very senior. Place of death: Northwatch Keep. But he was assigned to the Embassy itself– part of the standing security crew. Shouldn’t have been out at Northwatch Keep. At all. Not supposed to leave the premises unless on sanctioned leave.”

Ancano picked up his half-empty bottle and chose to drink it off. “Unpleasant fellow. One of Elenwen’s pets. Grasping. You know the sort. Pardon.” He stifled a belch.

“Anyplace else, we lose that many people in one day, we’d be ripping down buildings and setting everything on fire–” Ancano tried to slow himself down, he WAS drunk –”but our esteemed First Emissary does nothing. Nothing. Unfortunately I think…” he scowled. “I think that would be closely examined.”

He looked at Auryen Morellus, who wasn’t displaying any particular reaction. His face was wholly serene.

“Not even a formal expression of condolence to the families,” Ancano continued. “Very much unlike her– she spends a great deal of time keeping up face. And ever since then, the oddest allocation of duty assignments. Senior people left doing nothing but standing guard on empty buildings. Juniors assigned to hazardous duty out in the field. And the First Emissary herself, mostly-incommunicado, always anywhere-but-here. Chasing dragons. Allegedly.”

“Equally interesting that I’ve heard nothing either. No criticisms,” said Auryen. “Then again, the sheltering cloak of nepotism spreads awfully far, and Elenwen’s been the Third Council’s fair-haired girl ever since her esteemed parent put her up for consideration.” Auryen brightened: “Cheer up, at least no one will fault you now for not keeping the First Emissary apprised of your doings– it will be perfectly understandable given its context. Maybe they’ll commend you for taking such good care with the inquiry.”

“And maybe they’ll stick my head on a pike in some corner of a classroom in Shimmerene as a warning to all those who presume to climb beyond their station,” retorted Ancano. He dropped the pretense.

“You were right,” Ancano complained. “There’s nothing about any of the information you’ve given me that’s helpful– now all you’ve done is terrify me. What a–” He concealed a yawn–” horrible situation to be in. Lovely. I was already fairly motivated to try to get this young one healed to begin with; and now with what you’re saying– if I don’t, we face a full-scale Inquiry out of Alinor… and the probable recall of the First Emissary on suspicions of official misconduct.”

“Indeed. We’ve all nurtured a delicate balance here,” said Auryen Morellus. “I’d rather hate to see anyone else’s thumb on the scales.”

Ancano brooded.

Such a delight, Elenwen was– particularly when it concerned to awkward questions about her familial circumstances, control over her own subordinates, her presence or absence from her duty assignment, allocation of Dominion resources, general questions of competence…she’d certainly be looking for enemies to take down with her, regardless of whether or not she had perpetrated this outrage against her younger kinsman.

“I can get you your answers,” said Auryen, abruptly, interrupting Ancano’s dark thoughts. “Write down your questions, and I’ll have them taken to the Restoration mage, and then you–”

Ancano rubbed his face. “I’m afraid that would be too unwieldy, for the number of follow-up questions I would anticipate.”

There was further negotiation, blessedly brief. “If I cared to rank all the things that I do not care about, corruption-of-blood by some Dominion citizen who isn’t even a member of the Thalmor–” Ancano scowled. “Oh, of course, a Redguard from out of one of the formerly occupied territories. Who is likely, if I’m getting the generations right, a product of corruption-of-blood herself. I promise, I’ll try not to frighten these people. I didn’t even bring my blacks. So. Where is this mage?”

It was full dawn, now. No more time to waste.

Ancano scratched at the door, gently. He had managed to persuade a laundry maid to let him into the building, but it was still dark and quiet as its denizens slept. Thankfully he’d been escorted directly to the mage’s quarters, because even with the little he’d seen, this place was a dizzying labryinth.

There was movement. He tapped a bit louder.

The door opened just enough to allow the lady behind it to exit. Ancano blinked, because he had not been fully advised: this Redguard was truly lovely, with a sweet-faced expression that suggested a gentle disposition. He rather thought, looking at her, that even the Convention itself might let Master Lorion off with no more than a warning; it would certainly represent an excusable lapse.

She made a gesture for Ancano to be silent and shut it behind herself, leading him back out toward the main hallway. She settled herself in and sighed, as if her feet hurt.

“You’re one of those Thalmor,” she said, dubiously. “A Justiciar.”

Ancano smiled, tautly. “Yes,” he admitted. How in Oblivion did this creature– he was going to have to get out in the field more. Clearly he was out of practice. “Not why I’m here, though,” he said, tightly. “I wanted to get his professional opinion on a situation I’m monitoring; I’m a Restoration Master myself.”

“Of course,” she said, dimpling as if she’d read his thought. “You must be Master Ancano. Lorion’s often spoken of you.” She smiled up at him. “He always says that you were easier to get along with than Master Marance. He was sorry you’d moved on. Have you eaten? The food here is good.” She took in his evidently sleepless condition: “And if you like I could show you to a place where you can put your things down and rest.”

Ancano sighed. “I am in somewhat of a hurry,” he said. “There is a ship waiting on me. I can sleep once aboard. I’ll be ready for the interview as soon as he is.”

Lorion, when he finally came in, looked unutterably weary. For a few seconds Lorion looked almost pleased to see him, until Ancano related the information he’d come to share: That Ancano’d come to Lorion to beg his help, rather than to offer it.

Lorion was a mer drowning, and Ancano had thrown not an oar, but an anchor. His shoulders sagged. “Gods,” he swore. “How could I have missed that? How?!”

He looked at Ancano, a little desperate. “He would not let me look at him,” he remembered– “I got him to pull his tunic aside so I could deal with the gouges on his chest and arms and back– but he absolutely refused to let me conduct a full examination. Oh, gods. I should have pressed the issue. I could have had Sorex assist… he kept on refusing!”

“Not surprising,” said Ancano. “He had reasons to wish to conceal his injuries. What else do you remember?”

Lorion detailed what he’d done for the young Justiciar, running through each and every detail, trying desperately to find some symptom he’d failed to notice, some sign or signal. They spoke for some time.

“I wouldn’t beat yourself up,” Ancano advised, soothingly. “My main concern was whether anyone’d seen the abdominal injury whilst it was still fresh. It’s quite difficult to tell what it could be, now. But it seems like he was fairly active in the first few days after it happened? That’s heartening. So–” he frowned. “I’ll have to take the risk, I’m afraid, and send that note off to Evrard for him to get started.”

“The Ambassador lets me use his message-birds on occasion,” said Master Lorion, urgently eager to please. “I could go up there for you, or send someone… if you didn’t want to cause a stir. We could get that message sent to Winterhold today, and it might even be there by tomorrow.”

Ancano hesitated. “While I’m here– would you like for me to come in and take a look at your patient? Be happy to consult in if the family agrees.” offered Ancano.

Lorion was pathetically grateful to accept.

“You have got to be kidding,” said the Imperial, who’d grudgingly given Ancano his name: Sorex Vinius.

“Yes, Master Ancano’s a Thalmor Justiciar but he’s also a Restoration mage,” argued Lorion. “He’s been at Winterhold… um…just about forever.”

If by forever one meant five years– years which had been preceded by two and half decades’ absence. Ancano’d been perfectly content as one of Winterhold’s Restoration instructors, but that had been thirty years past. On the eve of the late war, Alinor had called its mages home. If he focused his attention narrowly, Ancano could almost forget those interceding years. Winterhold’s healers had walked their circuits, back then, before the Archmage’s prohibition. This negotiation with distraught family members was almost comforting in its familiarity.

“My training in the art of Restoration took place on Alinor,” Ancano said. “In Shimmerene, to be precise. But I did a great deal of practical work here in Skyrim, before I returned to the College and my new assignment.” He shrugged off this human’s hostility: “Currently I am the Dominion’s Advisor to the Archmage– they save all of that Concordat enforcement work for mer far junior to me.”

Lorion made his own further attempts at persuasion, to no avail. He looked at Ancano, beseechingly.

“Please,” Ancano said. “Master Lorion’s been of very great help to me today. I’d be obliged to you if you would allow me to return the favor.”

Sorex Vinus crossed his arms: “No.”

“Let him try,” came a voice from the other side of the doorway; a normally cheerful voice that grief had rendered leaden.

Sorex Vinius immediately backed down, as his father came into the room. “Ah. Alright. I’ll um– I don’t know what you need to–”

“Whatever you think can be done,” said Corpulus Vinius, exhausted. “I–” He regarded Ancano. “Anything,” he said.

“Would you mind running through it all again?” Ancano requested. “As if I know nothing.” He did know nothing.

Corpulus Vinius sighed. He rubbed his face. “You would have to ask the boy,” he said, huskily. “I don’t– I didn’t think it was serious at first and I was trying to keep up with all the work for the first few days…by the time we knew it was this bad, it was too late.”

“I was there,” said Fironet. “She fell over the chair and hit her head on the corner of the table. That Imperial officer said his men didn’t mean to do it, and Mariel told us not to take offense– that it was her own clumsiness. We thought it was just a swollen ankle, then. I mean, she hit her head, but that didn’t seem like anything much.”

She sighed.

“Her ankle was all puffed up, so she went to lie down and put it up. When she went to sleep, we all thought she was just tired…but after that she just never seemed to wake up fully.” Fironet shook her head. “We’d all been working around the clock, what with all of those people who were in here during the — um— incident. And then of course we had all of General Tullius’ men coming around to ask everybody questions.”

“Lorion had gotten caught up over near the Blue Palace,” she said. “He couldn’t get back to us for a couple of days. She was acting odd and drowsy. Said she had a headache. We thought she was just overtired. And then it got worse and worse.”

She regaled him with the details that Corpulus couldn’t. None were pleasant. All corroborated the already dismal clinical picture.

“Sorex was angry with Lorion for being gone so long,” she whispered, one eye on that worthy, who was angrily restocking the mead bottles behind the bar. “But what was Lorion going to do? He couldn’t get past the soldiers either. None of us were allowed to go anywhere at all. We couldn’t get help. And we even paid one of the soldiers to get a note up to the General– it isn’t fair!”

Sorex Vinius, passing by with a tray, interjected: “We held out as long as we could. And this is the thanks we get? Damn them! At least the Stormcloaks weren’t murdering us.”

“You need to be quiet,” said Fironet to Sorex, fearfully.

There were customers in the common-room. Drinking. And listening.

“It is an injury which has produced a condition similar to a type of apoplexy,” Ancano explained. “Sadly, there is not much that can be done once the disease processes of the body begin to run wildly amok.” Such as what had happened to the luckless Justiciar who was still awaiting Ancano’s return.

“All that one can really do is offer supportive care,” Ancano went on. “And hope that the body can heal itself. I can find no flaw in what Master Lorion has done for her; her condition is excellent for someone who has been in this state for awhile.”

“Is there any hope that–” Ancano cursed his own wayward tongue; he had let his thoughts carry himself too far adrift; and now this man was looking at him with unwarranted hopes that he would have to dash–

“My apologies for speaking in the theoretical,” he said. “In her case, there can only be one outcome.”

“It’s all very sad,” he said in conclusion. “But I don’t think that you did anything less than what could be done. These head injuries are tricky; you never know quite what will be. And by the time anyone knew there would be this much trouble, it was far too late to effectuate a surgery.”

Lorion nodded, glumly, and prodded unwillingly at the grilled fish on his plate.

“She’s in quite good shape for the condition she’s in,” said Ancano. “No one could ask for better care. It is unfortunate that there is nothing more that could be done.” Save for calling in the Arkay priest; but as that fellow had been eating his breakfast in the common-room, Ancano suspected that had already been done.

“Have you heard any news from Markarth of late?” Ancano asked, changing the subject. They spoke a little of other things; the newest postings, a bit of the society gossip here and there from Alinor. Ancano paid little heed to such things, and it surprised him that Lorion knew as much as he did. Knowledge gleaned is never wasted, Ancano supposed.

Fironet brought them more food; Ancano was surprised to find himself hungry. When he looked, the light from the windows told him that it was well past noon. There was something still bothering him about the young Justiciar’s injuries and the state of overhealing that Ancano’d found him in…he continued to mull it over.

When the Redguard girl brought him another cold cup of cider, he was surprised to find that he had come to a resolution.

“I will not need to bring your name into any of this mess,” he told Lorion. “Attending to superficial cuts and a few bruises? Too trivial for me to even justify the expense of bringing in an examiner and getting a formal statement.”

Much less the cost of sending this well-intentioned mer back to Alinor to face the wolves. Lorion nodded. He didn’t say much in response, but Ancano could see that he was breathing easier now.

“Since we have a little time,” Ancano suggested. “I know you couldn’t possibly render any opinion without having the opportunity to conduct your own examination– but perhaps you could review what I’ve observed thus far? I really don’t have much as much practical expertise on magickal backlash injuries as I’d like– this young mer evidently burned clean through all of his magicka in his efforts to heal himself…”

Lorion coughed diffidently and offered a couple of suggestions. He had never seen an overhealing injury, no– but he’d had to deal with a couple of Breton bards who had overspent themselves on Alteration magick in trying to keep their ship steady during a sea-squall.

They spoke for some time, their conversation wending its way naturally back to the subject of the woman who lay dying in the next room. Ancano had a few– a very few; Lorion was rather thorough– suggestions for her and her family’s comfort.

Lorion was still unhappy with the quality of his own work.

With any luck, Ancano’s unfortunate young colleague would someday be able to assure poor Master Lorion that he was faultless in this matter. The other healer-mage was still wearing an expression that Ancano knew too well: recounting every tiny error in judgment and every lapse in attention.

“Come down sometime and speak with Master Marance– I’m sure she’d be able to give you a much more critical review,” Ancano suggested, as he got up to gather his things. “You don’t have to worry about her going too easy on you– she doesn’t know the meaning of the word.” “I may do that,” agreed Lorion.

He seemed a bit more steady, by the time Ancano made his departure.

And with that, we’re done with Ancano– and we’re done with having to click through to Imgur!

All of the story excerpts going forward will be self-hosted, so they’ll be easier to see. Also, if you click on the pictures itself, you can scroll through all of them at once.

Over time I’ll work on getting the old posts updated to the new format. It’s going to take several weeks, though, because it is rather time-consuming. I think it’ll be worth it in the end.

Recent Comments